You don't need to be a theoretical physicist to go to the opera but it helps. Black holes, big bangs, general relativity and gravitational collapse, not to mention two solo flights to the abyss, one in virtual space at the Southbank and one in moral space at Glyndebourne, took on musical form this week, with varying success.

There's nothing new about composers trying to represent the cosmos: think of the murky C minor meanderings of Chaos in The Creation before the blazing, shattering yell of "Let there be Light", in bright C major. Haydn travelled to Slough to peer at the universe through Herschel's telescope shortly before writing his choral masterpiece.

More than two centuries later the American John Adams, never afraid of earthshaking subjects, wrote his opera Doctor Atomic, about Oppenheimer and the first atomic bomb test at Los Alamos. As it happens, Adams's orchestral digest of the work, good as a precis if not convincing as a standalone symphony, was heard this week, together with a new work by Philip Glass, of which more shortly.

But more fuss and attention surrounded a new staging, after a long gap, of Adams's I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw the Sky, in a collaboration between the Barbican and Theatre Royal Stratford East. The title, terrible as a concept and pretty awful for the name of a piece, was a quote from a survivor of the 1994 Northridge earthquake, which devastated part of the northern Los Angeles area.

Described as a "songplay in two acts", the project dates from the mid-1990s. Adams had already completed two large-scale operas, Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer. In comparison, Ceiling/Sky is a baffling ugly duckling: seven characters tell their intertwining stories through song, in a variety of jazz, blues and Motown styles, to a text by June Jordan. There are no jokes, which would have given it a Sondheim feel. Those seeking a play will want more words and character; those hoping for opera will feel short-changed.

Yet since this is Adams, each number is inventively written, rhythmically fiendish and expertly played here by a small ensemble dominated by electric guitar, sax, clarinet, keyboards and drumkit. I have heard Ceiling/Sky once before, and the impact was identical: just as you are keen to go home, two-thirds of the way through, the earthquake strikes at ear-piercing volume and the emotional temperature shoots up. You engage with the characters, but only in the nick of time.

The versatile young music-theatre cast, conducted by Clark Rundell, was outstanding. Directed by Kerry Michael and Matthew Xia, the simple staging had a community-theatre feel: not a bad thing but patchy in quality – at times brilliant and slick, at others limp. The women (Cynthia Erivo, Anna Mateo, Natasha J Barnes) sang their naughty-girl trio deliciously and the men (Leon Lopez, Stewart Charlesworth, Colin Ryan, Jason Denton) all deserve mention.

At the Festival Hall, Adams's Doctor Atomic Symphony was played as a prelude to Icarus at the Edge of Time, a performance piece combining Philip Glass's music with a retelling of physicist Brian Greene's children's book of the same name and a film by Al and Al. It was commissioned to mark the 350th anniversary of the Royal Society. Actor David Morrissey narrated while visuals of intergalactic maggots whizzed exquisitely around the screen before hurtling towards their doom.

So there was a lot going on. Marin Alsop conducted and the LPO delighted in the swell and heave of Glass's oscillating, live film-track score. As the doe-eyed boy Icarus flew towards infinity, so rapid string figurations were offset by expansive slow brass melodies, a reflection, maybe, of the notion of time moving slower as you approach a black hole. The best part was Greene's introduction, which was a kind of quick-quark crammer. The original myth of Icarus is more daunting and resonant than anything here, which was all perfectly enjoyable twaddle. Coming soon: Princess Dolly Meets the Boson?

On the subject of black holes, no one ends up in one blacker or more chasmic than Don Giovanni, Mozart's rake who is swallowed up by hell. Glyndebourne's new production, conducted by Vladimir Jurowski and with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, began with a big bang: literally, in the form of the solemn opening chords of the overture. In his first Don Giovanni, Jurowski spun vivid timbres from the period instrument ensemble, with delicate colours in the fortepiano-dominated recitative accompaniments. Tempi were brisk, with a sense of momentum carried from one aria to another, to the last bar.

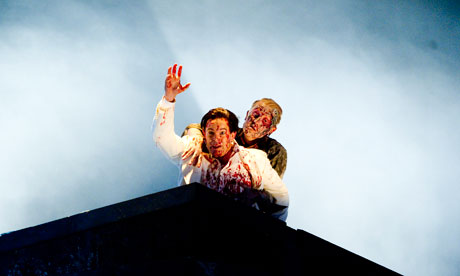

All in the pit was more assured than the action on stage. Directed by Jonathan Kent, who takes a somewhat cool approach, the production is set in the late 1950s. Paul Brown's revolving, rusticated box set creates a keen sense of the haphazard as all collapses in on itself, but it spins a few distracting times too often. The flames, providing excitement before the dinner interval, come too early making the end low key instead of electrifying.

The women look good, straight out of Fellini, but are undercharacterised, and none hits the mark musically. Kate Royal remains too sensible to convey the tempestuous obsession of Donna Elvira, the kind of woman who would not stop at cutting off a man's trouser legs. Her insane, vengeful "Mi tradi" should personify dark matter. Royal isn't there yet but, as with Anna Samuil's Donna Anna and Anna Virovlansky's Zerlina, she gives an assured performance which will develop as the run continues.

The men provide more grit. William Burden's Don Ottavio turns the delicate "Dalla sua pace" into a show of muscularity. Luca Pisaroni shuns that annoying wink-wink tendency which afflicts some Leporellos in favour of a sardonic charm, competitive with that of his master. As for Gerald Finley, an irresistible Mastroianni lookalike, vulgar in white tux with slicked back hair, he sang the Don with customary intelligence and expression. You can see why Zerlina weakened. Was he just too nice?

One moment in particular stood out: his serenade, as he comes close to his own cataclysm, was controversially but convincingly slow and lingering. Like Icarus he is at the precipice, and time passes sensuously slowly. This opera should leave you burnt to a frazzle; horrified by man's immorality and greed, flabbergasted by the intricate layers of plot and character, above all bewitched by the music's sublime invention.

The last was true. Listening to Mozart, you can believe high science and music a unified thing, as in that Pythagorean dream of the music of the spheres. The two have come together elsewhere this month: scientists at the Large Hadron Collider have simulated in electronic pitches the sounds made by sub-atomic particles. Try googling LHC Sound and hear the music of the nanospheres. It may make the star charts yet.